Investment and Irrigation on an American Indian Reservation

A lack of access to investment capital on American Indian reservations limits more efficient use of water through sprinkler irrigation.

American Indian farmers and ranchers provide an important economic base for rural areas in the Southwest United States. Yet the legacy of laws and rules associated with the US Indian reservation system creates a unique set of challenges these farmers must overcome.

One key challenge is land ownership. Tribal land on reservations is actually owned by the US government and held in trust for the tribe. This type of ownership (tribal trust) is characterized by cumbersome bureaucratic processes, limits on agricultural lease flexibility and the inability to use land as collateral to acquire loans.

Because of this, tribal farmers often lack the access to investment capital that is available to their neighbors who have full decision-making authority over their land (fee simple ownership). A lack of access to capital can prevent otherwise profitable investments from being undertaken, leading to reduced economic performance.

In the western US, irrigation technology is one of the largest categories of on-farm investment. CEnREP affiliate Eric Edwards and co-authors recently published a paper in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics examining how capital access affects investment in irrigation technology on American Indian reservations.

“Farming on tribal lands in the Southwest will become progressively more challenging in the future due to the decreased water availability and extended droughts predicted under a changing climate,” says Edwards. “It is critical to understand what institutional barriers, like access to capital, might impede the ability of these already vulnerable farms to adapt to these changes.”

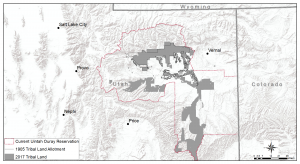

The study focused on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in Utah, which averages less than 11 inches of precipitation per year, making irrigation essential for any sort of agricultural production. The authors use an historic land allotment from 1905, which moved a large number of otherwise similar parcels out of tribal ownership, as an experiment. They test whether the parcels, otherwise similar except for whether they were fee simple or tribal trust, were utilized differently in terms of irrigation investment.

The paper’s findings suggest large effects: tribal trust land was about 32 percentage points less likely to be irrigated by sprinklers compared to fee-simple farms and had an average of 4-10 percentage points less land area planted with high-value crops, such as a corn and beans. Tribal-trust land is more likely to be irrigated via flood approaches, which require less investment because they pour water over a field directly.

Because trust land looks similar to the compared fee-simple land in terms of land quality, likelihood of being cultivated, and overall level of irrigation, the authors conclude that it is the ability to access investment capital for irrigation systems, not attributes of the land or people farming it, that drive the difference.

To solve the problem, farmers on reservations need improved access to capital, but more work is needed on how to accomplish that. Says Edwards, “At the beginning of the project, we set out to clearly show that incomplete land property rights as a result of federal trust ownership reduced investment in irrigation. In presenting our work to tribal stakeholders in the Southwest, we’ve learned there are several additional issues – including discrimination and red tape – that need to be overcome. The next step is determining what concrete steps can be undertaken to accomplish this.”

The paper can be found here.