Challenges of adjudicating Native American water rights in the western United States

A changing climate is expected to disproportionately impact vulnerable populations like Native American farmers and ranchers. Because their lands are primarily located in the Southwest, scientists predict they will see warmer temperatures and extended droughts. CEnREP affiliate and ARE assistant professor Eric Edwards is working with tribes tackling these challenges as co-PI on the Native Waters on Arid Lands project funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

The project joins researchers and extension specialists with representatives from nine tribes and reservations of the Great Basin and American Southwest. Together, the group collaborates and plans for ways to adapt to changing water needs and to enhance climate resilience on tribal lands. Edwards recently joined Tufts University Ph.D. candidate Leslie Sanchez in presenting research and engaging in discussions with tribes at the project’s fifth Tribal Summit in Reno, NV.

Their work, co-authored with Bryan Leonard at Arizona State University, suggests that increasing water scarcity drives tribes to resolve their claims to water in a legal process called adjudication. An historic 1908 Supreme Court case (Winters v. United States) ruled that western US Native American reservations hold reserved water rights, but tribes are responsible for quantifying their water rights through the adjudication process. However, these legal proceedings take an average of 25 years and are extremely costly. By collecting data on the settlement process, the researchers have identified key factors that increase the difficulty of negotiations. For instance, negotiations with a large number of water users take longer.

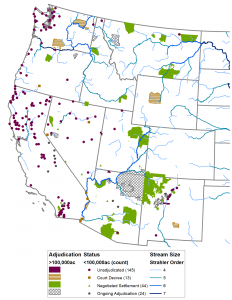

The map at left shows the reservations in the western US and the status of their water right claims. To date, only 56 of the 226 federally recognized reservations in the West have legally defined their Winters water rights.

At the Tribal Summit, Edwards and Sanchez shared their research findings with tribes at various stages of the adjudication process, then engaged in an open-ended discussion on a variety of issues.

Tribal members who had adjudicated shared their experiences, both good and bad, and answered questions on their experiences with the adjudication process. In general, tribes adjudicate to resolve uncertainty. They exchange their “paper” rights for “wet water,” but in the process have to give up some of the water they were originally promised by the federal government.

While secure water rights allow farmers to better plan for climate change, the water itself is just the first step. Many tribal farmers and ranchers have difficulty accessing capital in invest in their operations. This means tribal irrigators may still not be able to invest in state-of-the-art irrigation systems, even when they have secure, adjudicated water rights (see CEnREP Working Paper 18-017 for more details).

Further, most tribes do not have the infrastructure to divert their adjudicated water rights at the time they sign an adjudication agreement. Often, the federal government will step in and provide funding for irrigation and other water diversion projects, but this takes time.

As the Native Waters on Arid Lands project wraps up in the coming year, questions about the role of adjudications in tribal climate resilience remain. Edwards, Leonard and Sanchez are working on a follow-up project to understand what happens to reservations after adjudication agreements are reached, and how long it takes for changes to occur.